How much??

David Walsh, Jane Clark + Luke Hortle

Posted on Monday 14 April 2025

Next week, our Namedropping exhibition will close. David says that what he’s trying to do in this show is figure out what status is and why it is useful, in a deep sense—as part of our evolved biology. Namedropping is a light-hearted look at all that, with a few pauses for self-scrutiny. What follows is from the exhibition. Read more about Namedropping here.

How much??

By David Walsh

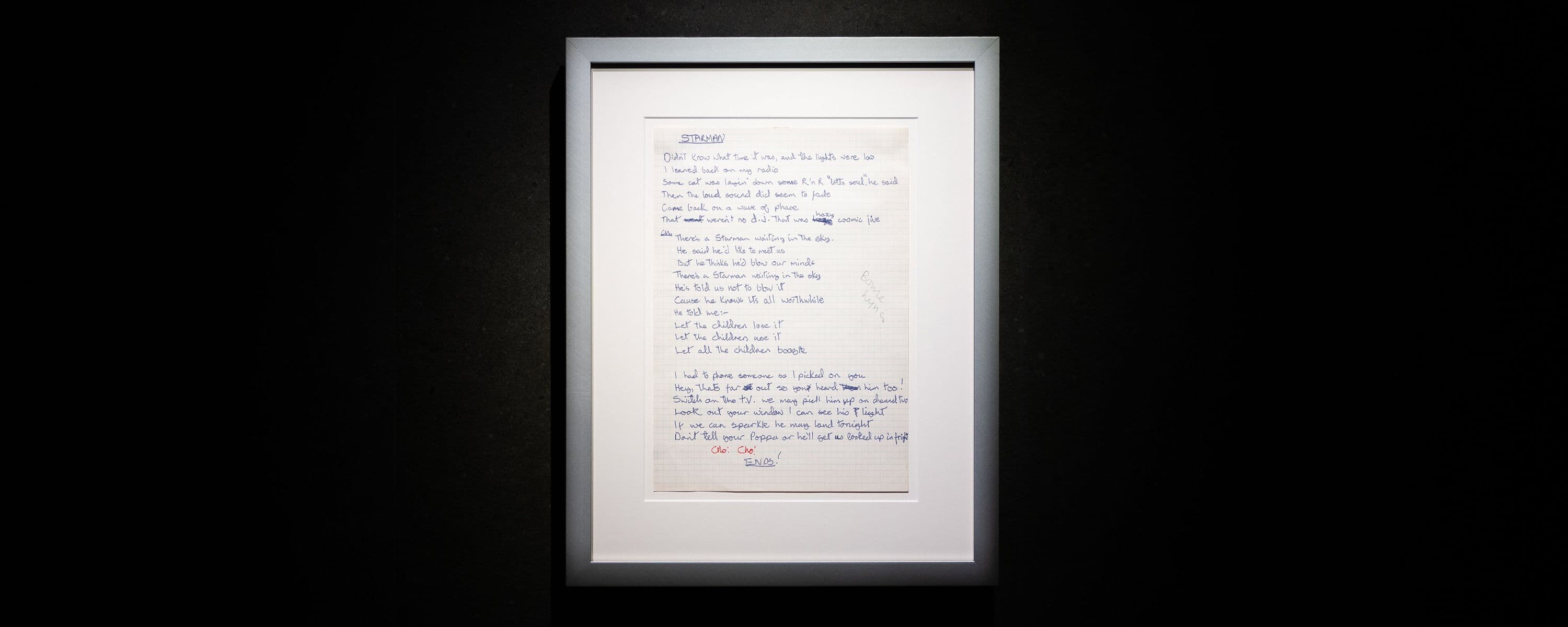

How much is a piece of paper worth? Not as much as we paid for this one. I told my colleague Olivier to bid up to £110,000 (too much). He bid £165,000 to secure it.* This piece of paper has written on it the lyrics to David Bowie’s ‘Starman’, not one of my favourites of his tunes. It’s a song, not a poem, and you can listen to the intended product on Spotify for nothing (if you’re prepared to put up with the ads), so why might this rendition of only the lyrics be worth even the £40,000 that the auction house estimated? (After all, it’s the performance that made it famous; after watching Bowie’s seminal performance of ‘Starman’ on Top of the Pops, Ian McCulloch, who would become the frontman for Echo and the Bunnymen, stared at Bowie’s groin thinking, ‘I’ve got a lot of puberty to do.’) Well, it makes the point about Namedropping, so it has come in handy for this exhibition, but is this piece of paper more useful than, for example, the 376 eye operations in Nepal that that money could have paid for?

*At Omega Auctions, 27 September 2022; and the auction house buyer’s premium made it £203,500 (equivalent to AU$386,000).

Hey, that’s far out …

By Jane Clark

What makes this piece of paper so special, when it’s the performances—Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars and their music—that made it famous? We hope you’ll realise by now that we put it down to ‘essence of David Bowie’. For anyone who’s a fan, these lyrics to ‘Starman’, inked in his own hand on graph paper, complete with his crossings-out and spelling corrections, are imbued with his genius—perhaps even something of his ‘soul’. For us curators, and perhaps for you reading this blog, David Walsh paying £203,500 to put the page in his private Museum of Old and New Art may well have added some essence of Walsh—his interest, his ownership, his now-quite-famous Mona—to that essence of Bowie.

There’s a rich mix of documentary evidence and retrofitted mythmaking around exactly when this manuscript was penned early in 1972. It’s possible that Bowie first conceived ‘Starman’ late the year before.1 But we know that he and his backing band—the Spiders—recorded the song at Trident Studios in London on 4 February 1972 and it’s claimed by various associates and biographers that he wrote it that same day. At that point, it wasn’t slated for the album they were working on, The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, but RCA’s New York R&A executive wanted a potential hit single included. By March, ‘Starman’ had replaced a cover of Chuck Berry’s ‘Around and Around’ on the album and it was remixed for the single. According to the manuscript’s previous owner, Bowie wrote out these words for printed lyrics on the album’s inside record sleeve (just a few words differ). So, current research suggests, pen to paper sometime between 4 February and 27 March 1972.2

The single was released on 28 April; the album on 6 June. But it was the performance of ‘Starman’ on BBC television’s weekly Top of the Pops on 6 July that made David Bowie a star. His sexually ambiguous alter ego, Ziggy Stardust, burst into millions of sitting rooms wearing the body-hugging spacesuit he’d cribbed from Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (the film had opened that year), red lace-up boots, dyed red hair and makeup and cosmic jive. The song was widely received as Ziggy’s message of hope to Earth’s youth—‘Let all the children boogie’, ‘Don’t tell your Poppa’ and ‘If we can sparkle, he may land tonight’—even if Bowie later said it wasn’t. Its dreamy opening chords refer back to his own ‘Space Oddity’. The chorus is inspired by Judy Garland singing ‘Over the Rainbow’ in The Wizard of Oz (1939) with other ‘namedrops’ including the Supremes’ hit ‘You Keep Me Hangin’ On’ (the morse code sounds) and Marc Bolan of T. Rex (he’s the cat laying down some rock ’n’ roll). According to one of Bowie’s keyboard players on the Ziggy Stardust UK tour, it’s ‘one of the great rip-off songs’. On the other hand, as Dylan Jones writes in his biography, When Ziggy Played Guitar: David Bowie and Four Minutes that Shook the World:

Many of those who saw David Bowie perform ‘Starman’ on the BBC in the summer of 1972 have never forgotten it, and it sits there, on a tatty old loop in our memory bank, reminding us that we were once both very young.3

1. He was reportedly thinking about a ‘Stardust’ character in 1971. There’s an extant rehearsal recording of ‘Starman’ said to date from late 1971, sold at Omega Auctions in 2019; however documented rehearsal sessions suggest this was more likely January 1972.

2. According to biographer Kevin Cann, the RCA New York artists and repertoire man, Dennis Katz, complained on 2 February 1972 that there was no radio-friendly single on the album (see David Bowie: a Chronology, 1983 and Any Day Now—David Bowie: The London Years: 1947–1974, 2010). The album’s 9 February master reel does not include ‘Starman’ but the 27 March master reel does; with Bowie, Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder and Woody Woodmansey. On 27 (possibly 28) March, Bowie, Ronson and producer Ken Scott remixed ‘Starman’ for the single release.

3. Nicky Graham quoted in Lesley-Ann Jones, Hero: David Bowie, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 2016, p. 126; Dylan Jones, When Ziggy Played Guitar: David Bowie and Four Minutes that Shook the World, Preface Publishing, London, 2012, p. 1. See also Benoît Clerc, David Bowie, All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track, Black Dog & Leventhal, New York, 2022, pp. 138–147; and The Bowie Bible at www.bowiebible.com.

For posterity

By Luke Hortle

Mona’s conservators calculated how long we should put these lyrics out on display, without causing undue damage. Their expertise took into account things like exposure to light, consequent fading over time, quality of the ink (not great) and paper (cheap, acidic and thus prone to yellowing). All this balanced against the value of you being able to look at them when you visit the exhibition. They advised, for optimum preservation, showing the page for three months at the start of the exhibition and three at the end, leaving a four-month gap in the middle when it would stay in storage in the dark. This, they said, would allow us to display the lyrics safely for the next 70 years and potentially for 600.

To which David said:

I think it’s amazing that, to us, ‘Starman’ is worth more than the Magna Carta is to the British Library. I’m going to put it on display for the duration.

And:

Just to explain a bit more, let me ask you a question. Who was the most famous British songwriter 70 years before Bowie? This object is 50 years old. In another 70, I don’t think it’ll have any cultural relevance at all. Bowie isn’t the Beatles, and he isn’t Beethoven. His importance arises because those of us who liked him 50 years ago are mostly still alive. It is most valuable now. Indeed, I suspect that, if we preserve it, we would be preserving it for a posterity to which it would be irrelevant.

So here is David Bowie, for you to enjoy—today. Or try your luck and come back in 2095 (or 2625).

Header image: ‘Starman’ lyrics, London, January–February 1972, David Bowie

Ink on paper