All in good taste

Painter, 1995, by Los Angeles artist Paul McCarthy, regularly tops our list of works most hated by Mona visitors. I have avoided writing about it for a long time, because that would entail sitting through the whole thing: fifty minutes of unpleasant muttering and groaning, thrashing wildly around with paint, pissing in pot plants and squeezing shit out of an oversized tube onto a canvas, topped off with a really (sorry to be a prude) distasteful bum-sniffing montage at the end.

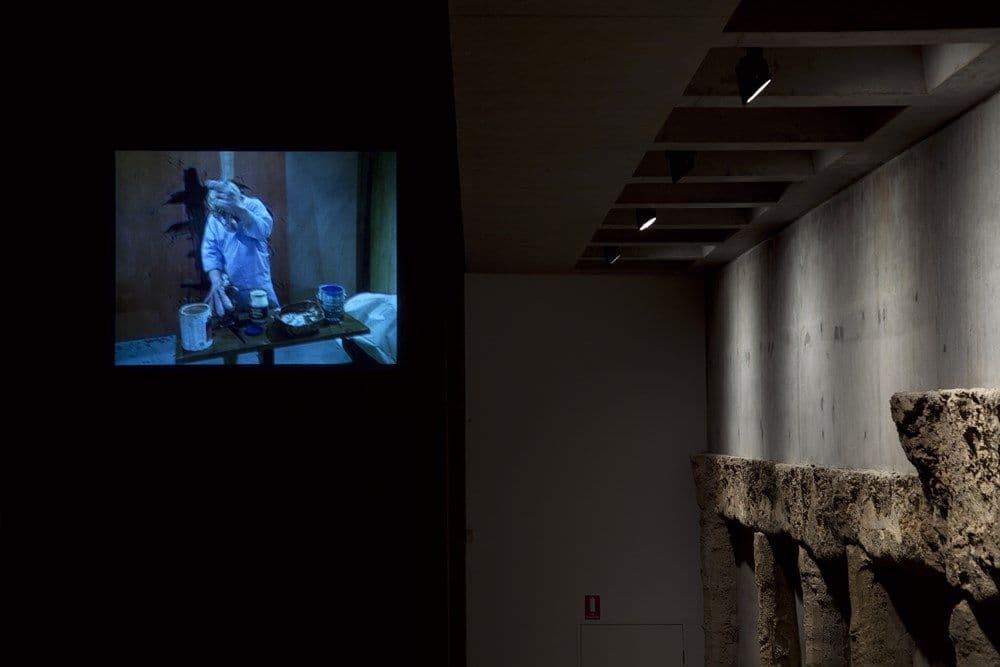

Left: Painter, 1995, Paul McCarthy

Right: Paul, 2014, Ronnie Van Hout

Photo Credit: Mona/Rémi Chauvin

Painter, 1995, Paul McCarthy

Photo Credit: Mona/Rémi Chauvin

Needless to say, I find it difficult too. I think it’s got some merit, though. For me, it’s the sheer weirdness of the thing, the angsty-funny, sex-fiend-in-a-clown-costume atmosphere it generates; and, on a more cerebral level, the way it exposes and exploits the myth of the male artistic genius.

So, obviously Painter is a parody of the process of making a painting. It comments specifically on the American ‘action painters’, also known as the abstract expressionists: the group of artists, led by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and others, who came to prominence after World War II, shifting the centre of the artworld from Paris to New York. The title character in Painter (who is McCarthy himself of course) chants ‘de Kooning’ under his breath as he works, channeling his spirit, or trying to free himself from his daunting legacy. In contrast, the scene of the interview with the inert European collectors shows them mindlessly listing their trophy-buys. ‘What Rothko do you have?’ asks the dullest interviewer on earth. ‘A brown one,’ the male of the pair replies. ‘It’s red actually’ says his wife.

This kind of commercial cynicism is common to the artworld of course, but it juxtaposes especially sharply with the central objective of abstract expressionism, which is to externalise an authentic inner reality. Among diverse styles and techniques was the common goal to express an interior psychological state – delivered via the medium of movement as much as paint. Putting paint on the canvas was a kind of performance, and the resulting painting a document of an authentic moment in time. This was ripe for myth, in part because it taps into our intuitive feelings around art and authenticity: underneath our suspicion of the pretentions of ‘the artworld’, we like to imagine there is such a thing as submerged essence of genius, just waiting for release.

This collective fantasy took shape around the macho dudes of the movement. ‘If the women could see me now, oh boy…’ says McCarthy’s painter – but he’s less potent than pathetic, a child saddened and enraged by the unwillingness of the universe to revolve around himself. ‘I can’t do this anymore,’ he cries on repeat, in a way I find especially uncomfortable; he might mean painting, or life. The other major hallmarks of the action-painting myth are present as well, in his emotional volatility (sobbing and whining one moment, calling on God for inspiration another), physicality (hacking, pumping, jabbing maniacally at the canvas), and diva demands. ‘I want all the money right now,’ he shouts at his gallerist. ‘I want shows all over Europe, and I want big, big catalogues!’ ‘You’re acting like a spoilt child,’ she replies, ‘You’re going through a stage. All the artists who get famous go through this. You’re just a human being. Stop this ridiculous tantrum!’

This is self-parody, too, of course; McCarthy himself came to prominence in the 1990s, around the time Painter was made. The aesthetic of his work – sort of like a cross between a porn set and Disneyland, in which at any moment the characters will start rubbing themselves on each other or chopping off their rubber limbs – is a reflection on his sense of place, of the difficulties of making original and meaningful film and performance work alongside the Hollywood dream machine. His intention, too, to comment on mainstream American culture is shown in his trademark use of foodstuffs like ‘ketchup’ (as they call it), mayonnaise, and chocolate sauce (stand ins, he says, for blood, semen and poo). McCarthy has been using these foodstuffs in paintings and performances since the 1970s. This connects him to the Viennese Actionists of that time, the difference being (as McCarthy himself has made clear) that they were using real bodily fluids, and causing themselves real physical and psychic pain. McCarthy is more interested in buffoonery than trauma, I think, and yet a sense of trauma is, for me, most certainly conveyed.

In the process of writing this, I started to go down the rabbit hole of art history, and it occurred to me that I might be becoming a wanker. (That’s a nice mixed metaphor: wanking in a rabbit hole.) Claiming to like and ‘get’ difficult conceptual art is a marker of the ‘in’ group, as distinct from the taste and preference of ordinary people. This very discrepancy is part of what drives the trajectory of modern art history. Quentin Bell (following Thorstein Veblen) identified the phenomenon of ‘conspicuous outrage’: I have so much cultural capital, I can afford to flout ‘good’ taste. I decided to send my essay to David for feedback. Maybe I should have stuck to my initial reaction to Painter, and not worried about this artworld palaver. Here’s what I wrote in an earlier draft:

I don’t like Painter because: it looks kind of crappy, like a student porn film; the squeaky voice is annoying and creepy; nothing really happens; the painter character is sad and pathetic; the prosthetic noses freak me out; the bum sniffing at the end is really, really gross.

And another:

I feel anxious when I watch it, and sad, like being confronted with the inherent loneliness and ridiculousness of ‘the human condition’ (that old chestnut) – and I don’t agree, and even if I do on some days, I don’t want to be reminded of it. I don’t see that scraping the barrel of our doubt and insecurity just for the sake of it is valuable, nor that shattering taboos is inherently worthwhile. I sound like a thousand other ranters on the internet. I am getting old.

And finally:

Just so you know, this is not going to be one of those ‘she does like it, after all, because it shows her the underside of her own fears and desires’ or some such rubbish. I’m pretty sure I will still hate it after I’ve finished writing this, and that will be because it’s crap, not because of some character flaw of mine.

Works like Painter reflect, in part, a process by which the cool group selects the most outrageous art to represent it, pushing artists to invent more and more outrageous means to stay ahead of the curve. McCarthy knows this, and therein lies the strength of his work. But in the meantime, the work is still ugly and unlovable. It dares me to embrace my authentic response. The only reason I started to think more deeply about Painter, to try harder to like it, is that it has been sanctioned as ‘significant’ – by art history, and by the gallery that employs me. But then I did, truly, start to like it more. ‘Truly’. Is it really ever possible to approach a work of art in and of itself, without the surrounding social and cultural context? Art isn’t just sensory input, after all – patterns and colours and pretty shapes. It tells human stories, and humans are cultural and social – intensely so. Surely an ‘authentic’ response should embrace this as well?

David wrote back to confirm that yes, I was becoming a wanker. But he also added this:

My mother used to tell a story about World War II army rations. One wasn't allowed to complain about the food; the penalty was to be assigned cheffing duties. A ‘chef’ attempted to get his duties reassigned. He cooked camel turd. One person exclaimed, ‘This tastes like shit,’ and then, collecting himself, continued, ‘but the servings are substantial.’

McCarthy's marvellous parody has tension because he is biting the arse that feeds him. Art (and the art market) can be shit, indeed. But the servings are substantial.

Thanks, David, for summing up what I think I’m trying to say, and also for adding another metaphor to this overloaded essay. But mostly for letting me… um… bite the arse that feeds me… Oh Lord. I think I’m done.